High above Hobart, Tasmania’s capital, looms Mt. Wellington. From the summit, at about 4200 feet, Hobart and the Derwent River gleam in the hyper-clean, frigid and sunlit air. Getting up there, and being there, were breathtaking, in a teeth-chattering sort of way.

First, getting there, on a narrow curvy road. A road so narrow that this really happened, because I couldn’t make it up. I was on a tour bus, you know, a regular bus-sized bus. And the road was basically a lane and a half for two-way traffic, so that when we came upon a piece of construction equipment parked at the edge of the oncoming lane, with no driver in sight, a passenger from my bus had to get out and flip in the mirror of said traffic obstacle so that our bus could get by. And we squeaked past just a bare mirror-width apart, as passengers on that side of the bus squealed, and then spontaneous applause broke out as we all stopped holding our breath and realized that we would, indeed,

manage to make it to the summit. Whereupon virtually all of the passengers began pulling jackets and even parkas out of their bags, having all, apparently, read that you can get frostbite on a sunny early autumn day up there. Whatever they had read had completely escaped my attention, so that I was wearing only a cotton shirt. The wind was whipping and people were shivering and exclaiming in a dozen languages, even though they were jacketed. I wasn’t saying much, probably because my lips were frozen together.

Mainly I was just trying to take a few pictures before my fingers got too numb to hold the camera. It’s a gorgeous spot, and worthy of much more time than I could afford to spend before suffering hypothermia.

But I appreciated the way these unexpected little flowers displayed the essence of adaptation, blooming without a care in such a harsh environment.

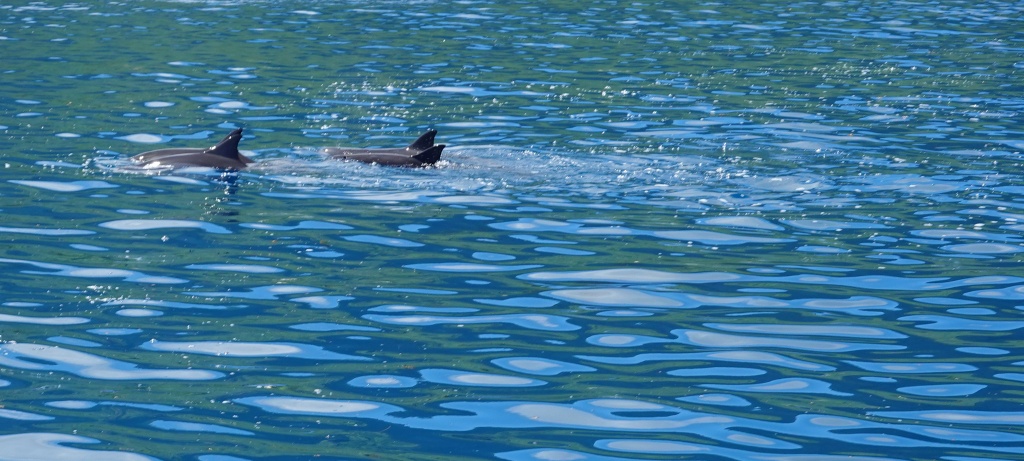

Speaking of the unexpected, after descending back into Hobart I took a ferry to MONA, the Museum of Old and New Art, which might as well be called the Museum of Unexpected Art. To get there we sailed under the Tasman Bridge

and past the Risdon Zinc Works, which from a distance looks like a piece of industrial art.

MONA is built underground, so all of the architectural interest is inside. It’s a three story museum built into the hillside, a sort of cave, and it houses some of the most provocative, sophisticated in-your-face art you would ever want to see. I’ll give you a little taste of what it’s like in there, because a bigger bite would include a lot of art that’s definitely NSFW. Really, go to Tasmania just to go to MONA. It might be the wierdest and most rewarding thing you could do.

Much of the place is carved out of sandstone. Even the walls are shockingly beautiful,

and bridges lead you between various galleries. Lead might be the wrong word, misleading even. MONA is a confusing place to visit, intentionally. There are museum staff members stationed in every conceivable corner, and when I asked one if there were a map to the place, since there are not really any signs telling you how to get to any particular gallery, she told me “Sure, there’s a map, but it’s not really the way to see the art. The best thing you can do is just to get lost in here.” So I did let myself drift through the place, using the fantastic app they have to give you the details about each art work. And if you want the deep dive, the full story of the art work and the artist, there’s a link for most pieces called the “art wank,” which gives you an idea about the irreverent tone of the place.

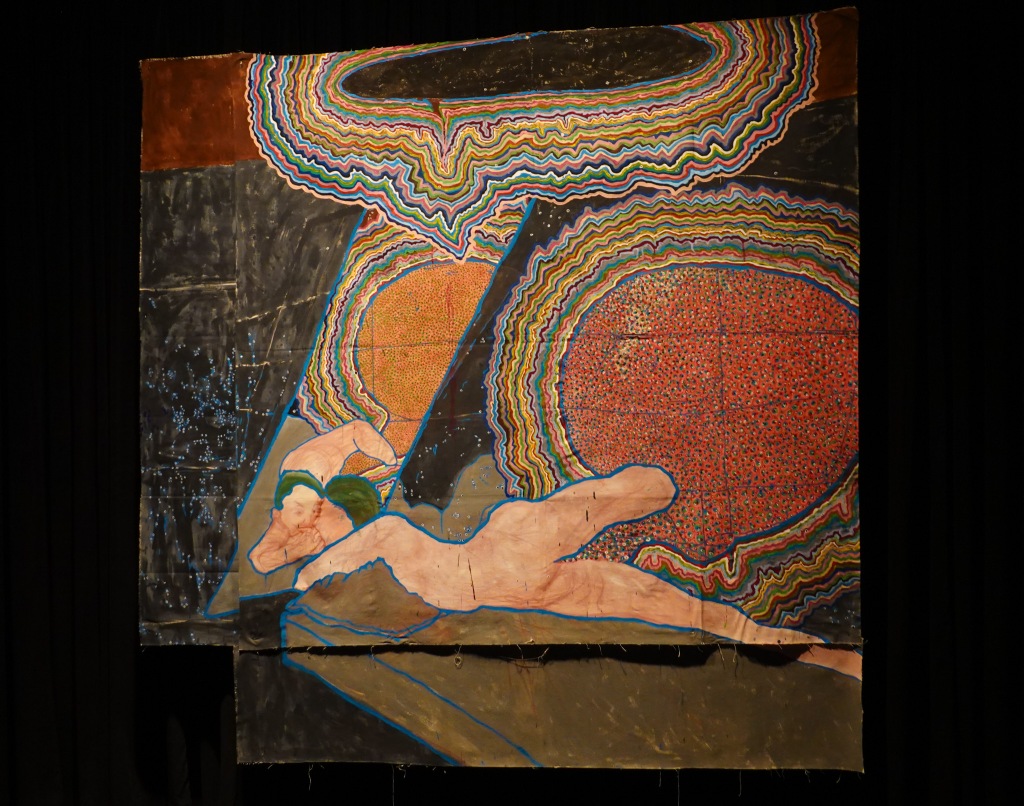

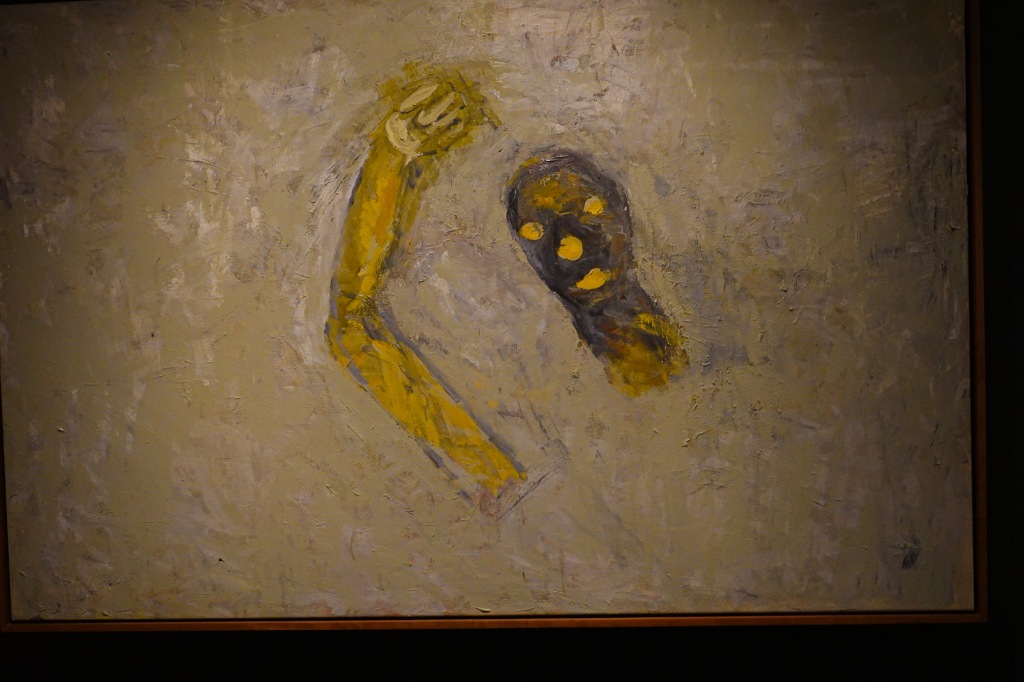

Here are a few pieces that struck me, and held still for the camera. Much of the art is lit in subtle ways that make it hard to photograph, and some of the pieces move and shimmer and change constantly. One of the most amazing is a sort of waterfall whose droplets form fleeting words randomly selected from the day’s Australian news headlines. Seriously. Each word forms and vanishes in the blink of an eye, and the whole thing is mesmerizing.

This last painting stopped me in my tracks for the longest time, although I cannot tell you why. There’s something about it that speaks volumes, at least to me.

This was perhaps the most disturbing work I saw, although I only had time to see about half of the whole collection, so perhaps it’s one of the tamer pieces. I’ll never know.

And then, this. I came upon a round table, with a few chairs around it. People wearing noise-cancelling headphones were seated at the table, each with a piece of paper, a small scoop of this rice and lentil mixture, and a pencil. The staff attendant asked whether I’d like to participte in this piece of performance art. I asked her what the performance consisted of, and she was very vague, saying that the instructions were to sort our your pile of grains into a pile of rice and a pile of lentils, then count each pile and write down how many grains of each were on your piece of paper. I looked around and noticd that the participants were running the stuff through their fingers in a variety of ways, but all looked calm and peaceful. After the sensory onslaught of the rest of the museum, lentil-sorting sounded appealing, so I agreed to give it a try.

But I was incapable of following the instructions and my fingers refused to separate, to count. As soon as I started touching the rice and lentils I began making patterns, and as each new pattern formed, since I had a pencil in my hand, lines began to write themselves. As you may or may not be able to decipher, this is what the rice and lentils said to me:

Poem in rice and lentils, black and white

Resisting separation, a fragile blending

Eternal sustenance, uncountable

Ephemera made tangible

Reaching backwards through time

A single difference jumps out, doubles, magnifies

Destruction and re-creation, endlessly

Words in the snow, one stands alone

The elusive power of human touch

Tasmanian peace

So that’s the little art I made, or the art that made me, inside the mysterious MONA.

There were a few art pieces outside, as well as another little performance space in the form of a trampoline. A young guy was jumping, doing tricks, and when I asked him to do one more somersault just for me, he gave me this:

And that’s what MONA will do for you, turn you around and maybe upsidedown. I hope I get another chance to visit in the future, and I hope you do too.